Poplar Island restoration brings critical habitat back to Bay

The island hosts shorebirds, waterfowl, raptors and other wildlife.

Part construction site, part mud pit and part wildlife refuge, the Paul S. Sarbanes Ecosystem Restoration Project at Poplar Island, Md., tackles two unique challenges in the Chesapeake Bay.

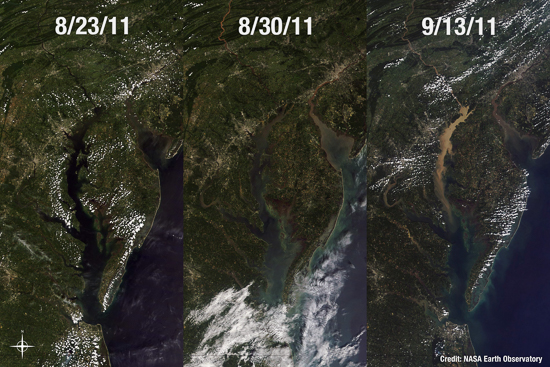

First, sand and sediment accumulate in the Bay’s vital shipping channels—particularly during heavy rain events like Tropical Storm Lee in 2011—and threaten to block cargo ships that allow the Port of Baltimore to contribute $2 billion each year to the region’s economy.

On the other hand, sea level rise, sinking land and increasingly frequent strong storms are quickly eroding away the Bay’s few remaining islands, threatening the survival of iconic wildlife species and critical habitat.

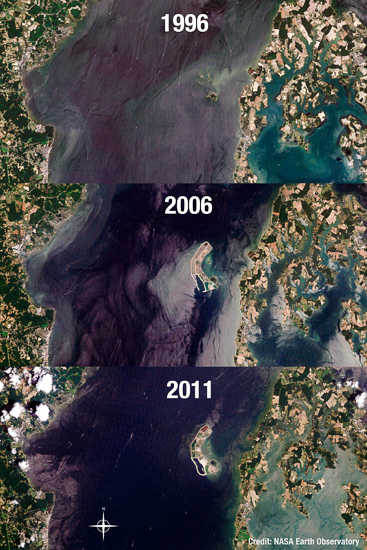

Poplar Island, for example, spanned more than 1,100 acres in the mid-1800s and supported a small community of families, farmers and fishermen until it was abandoned in the 1930s. When restoration began in the 1990s, four scattered acres were all that remained—less than half a percent of the island’s historical size.

But the island that was nearly destroyed is now destined to be rebuilt using 65 million cubic yards of sedimentary silt—imagine a giant cube of mud a quarter mile long in each direction—dredged up from the bottom of the Bay.

In 1998, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began to construct stone “containment dykes.” The walls are 10 feet tall and surround Poplar Island’s former footprint, and the island has been divided into six massive containment cells for building island habitat.

The western half of the island, surrounded by an inner ring of 27-foot dykes, is being transformed into 570 acres of forested upland island habitat similar to that of neighboring Coaches Island.

Coaches Island, once vulnerable to the same forces that washed away its neighbor, supports upland species like bald eagles and provides a shallow inlet utilized by nesting diamondback terrapins in the summer and migratory waterfowl during winter.

The eastern half of Poplar Island is further divided into 14 “sub-cells” undergoing various stages of wetland construction and management.

Low-lying wetlands are created through a four-step process. First, dredged sediment is brought in on barges by the Maryland Port Administration, mixed into a watery slurry, and pumped into each cell at precise levels.

As the slurry dries, it forms a massive crust—a vast, other-worldly landscape—that is the base for building habitat.

Next, heavy machines carefully grade the crust and excavate ditches that will function as tidal creeks in the completed marsh.

Then a spillway is opened to expose the new landscape to tidal flow, and water is allowed to move between the Bay and the newly built marshland.

Finally, individual plugs of smooth and saltmeadow cordgrass are planted row upon row into the nutrient-rich soil.

These native plants are capable of withstanding strong storms while offering food and shelter to the 175 species of shorebirds, songbirds, waterfowl and raptors that now visit Poplar Island.

Poplar Island's marshes offer protection and isolation from human and mammalian predators, and the open waters along its perimeter provide feeding opportunities for diving ducks like buffleheads, scaups and long-tailed ducks.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) manages the island’s vegetation and wildlife—including less welcome species like the Canada goose. Fences and fluttering pink flags help deter geese and prevent them from overfeeding on expensive marsh grass.

On our visit in January 2013, USFWS wildlife technician Robbie Callahan led a monitoring team to assess the density of muskrat huts in the marsh. The semiaquatic rodents, though a critical part of the wetland ecosystem, are controlled to prevent damage from overpopulation.

The USFWS also monitors avian predators—like the northern harriers that feed on small rodents—and migratory waterfowl, attracted to Poplar Island during their spring and fall trips along the Atlantic Flyway.

With the help of USFWS experts, Poplar Island is able to provide a range of Bay species with the safe nesting habitat that only a protected, well-managed island can.

Even sunken barges—placed here in the mid-1990s as “breakwaters” in an attempt to retain the island’s remnants—have become host to nesting ospreys and black-crowned night herons.

Piles of brush—created using old Christmas trees provided by the Maryland Environmental Service—help protect vulnerable species like black ducks during mating season.

According to the USFWS, Poplar Island is well on its way to becoming a keystone wildlife refuge. “Poplar Island is an important refuge,” said USFWS biologist Pete McGowan, who specializes in waterfowl and island restoration. “There are species that are highly dependent on these remote island habitats. And this is a habitat type that is rapidly disappearing from the Chesapeake Bay. We need to do what we can to maximize the remaining island habitat that we have, and create new island habitat whenever possible.”

The Paul S. Sarbanes Ecosystem Restoration Project is scheduled for completion in 2041, with a final price tag estimated at $1.4 billion over 45 years. Rebuilding Poplar Island is an enormous, expensive and painstaking process—but its virtues of “beneficial use” have been extolled throughout the conservation and business communities alike, and it has become a "win-win" for the Bay and all the watershed provides.

View more photos on the Chesapeake Bay Program Flickr page.

Comments

In the 70's my Dad and Mom and me ran his old, wooden Grand Banks there to anchor and enjoy. Often my uncle John Moll (the Chesapeake Bay artist joined us). Good times never to be forgotten. Great site and project. Maybe Chesapeake Bay can still be saved.

Thanks,

Bob Moll

We used to run across from Deale, MD in an 18' runabout in the late 1970s. It was an idyllic and uncrowded spot. The total land area at that time was around 10 acres as I recall. It was obvious that it was rapidly dwindling away. Sometimes the bluefish would chase menhaden into the shallow and somewhat confining area just east of the island(s) and in the shallow water would go airborne(6') trying to throw the lure. As I recall there was no salt march habitat remaining. Even then the primary food chain in the Bay had become algae-menhaden-bluefish rather than the more complex bottom based process. It is good to see such good use being made of the spoil and I hope strides can be made is improving light penetration in the Bay as a whole.

I was out there this morning on a tour with contractors interested in doing some spillway construction and repair work in anticipation of further expansion on the north-east end.

It appears to be a fantastic place that is only now really getting started. A few decades from now, with its uplands forests and wetlands really established and in equilibrium, it will be a world-class showplace.

Thanks for the picture show. Wish I had seen it before this morning's tour.

I remember boating near Tilghman in the early 1990s, with Poplar and Coaches Islands being tiny and vulnerable. This is an amazing and creative restoration of habitat, and it would be wonderful to offer the residents of Smith Island hope of a similar future for their homes and livelihoods. Next time on the Eastern Shore, we want to take the Poplar Island tour. Thank you for sharing this beautiful site. - Ted & Marci Turner, Hollywood, MD - St. Mary's County

Tours of Poplar Island are operated by the Maryland Environmental Service from March through October, and are open to school groups, community organizations and individuals. To make a reservation, contact poplartours@menv.com or 410-770-6503.

Can people visit Poplar Island?

What a lovely gift. Not only do we get to look at these great photos at our leisure, we also get a morale boost with good news about something "we've" done to impact the Bay in a positive way. I enjoy the videos on this site and think that photo essays are a viable addition. Keep up the good work, Steve. Thanks.

Great craftsmanship and message. I had the opportunity to fly over the Poplar Island site while representing Pennsylvania in the Chesapeake Bay Program; wondered how it was working out, as we have all had setbacks with well intended restoration efforts. Nature is often more resilient than we credit--if we work with her. Thanks for this encouraging update--we need to celebrate the positive while condemning the negative.

Great photos. Great article. Great work, Steve.

Gorgeous photos! The article was very informative and enjoyable to read. Thank you.

This was amazing to see and read. Nicely done, thank you!

Steve - These photos are incredible and a good reminder that sometimes we can create innovative solutions that work. Bringing new homes for wildlife while recycling waste from dredging. Due to its location, most people don't get to see this success story. You have brought it to life. Had a chance to visit Poplar back in the early 90's when this project was just beginning. Would love to get back out there sometime but this is the next best thing.

Thank you for posting this pictorial essay. We have driven past it by boat many times but cannot grasp how the project is working out. It looks beautiful and nice to hear it is a win-win for commerce and the environment.

I love the pictures. I learned a lot from your article. Great job!!

Poplar Island is one of the great success stories on the Chesapeake Bay. I would love to see Steve's pictures, with story, in all the papers in the Bay region on a regular basis to remind everyone that we can do the right things.

Great pictures! Article is very informative and well written.

Outstanding pictorial review of very important work!

Excellent article. Nice photos. Thank you, Steve Droter.

Breathtaking photography! Article is very informative and educational. Thank you for sharing.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories