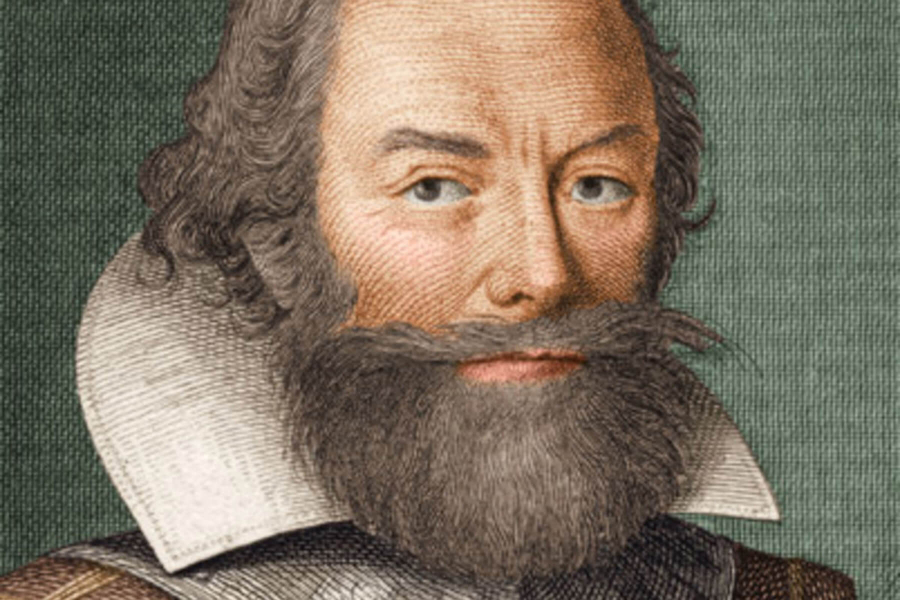

Captain John Smith

Travel along on the voyage of Captain John Smith, an English explorer who journeyed through the Chesapeake Bay.

Captain John Smith was an English explorer who played a pivotal role in settling America. His contact with native tribes and his Chesapeake Bay voyages, documented in maps and journals, helped early English colonists learn about the region that became their new home.

Smith's voyages

As a member of the governing council of Jamestown, Virginia, Smith led two voyages on the Chesapeake Bay. English officials instructed Smith and other colonists to map the area, claim land, find gold and other riches, trade with the natives and find passage to the Pacific Ocean.

During his journeys, Smith kept a journal of the incidents his crew experienced and detailed descriptions of what he saw. He charted the land and waterways, and later drew an elaborate and remarkably accurate map of the Chesapeake Bay.

Smith’s first voyage

On June 2, 1608, Smith and a crew of 14 men set out on a voyage up the Bay in a small, wooden boat called a shallop. Smith traveled north along the Bay’s eastern shore to the Nanticoke River. He then crossed the Bay and explored its western shore as far north as the Patapsco River.

Strong winds and complaints from his crew finally forced Smith to turn around. On their way home, they discovered the Potomac River. They spent several weeks there, searching for gold and dodging arrows.

Heading south once again, their tiny shallop ran aground on a shoal near the mouth of the Rappahannock River. Smith almost died when he speared a cownose ray and was stung by its poisonous tail spine. He recovered well enough by evening to dine on the ray. The area is still known today as Stingray Point.

Smith’s second voyage

Smith and a crew of 12 men set out on a second voyage on July 24, 1608. During this voyage, Smith made it all the way to the head of the Bay and the Susquehanna River.

On the second voyage, Smith and his crew encountered several native tribes. Some were hostile and attacked the men, while others were peaceful and traded goods with them.

Smith also explored the Patuxent, Rappahannock and Piankatank rivers before returning to Jamestown on September 7.

Smith’s writings

In 1609, Smith went back to England after he was severely burned in a fire. He never saw the Chesapeake Bay again.

Once he returned to England, Smith published his map and journals describing the Chesapeake Bay.

In one of his most well-known passages, he wrote:

There is but one entrance by sea into this country, and that is at the mouth of a very goodly bay, 18 or 20 miles broad. The cape on the south is called Cape Henry, in honor of our most noble Prince. The land, white hilly sands like unto the Downs, and all along the shores rest plenty of pines and firs ... Within is a country that may have the prerogative over the most pleasant places known, for large and pleasant navigable rivers, heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man's habitation.

Smith’s writings drew attention to the Chesapeake region and helped lure many English colonists to America. Today, they provide excellent insight into the Bay’s natural history before Europeans settled the region.

Changes since Smith's time

If John Smith were to retrace his 1608 Chesapeake Bay voyages today, he would need more than his original maps to find his way. Humans have dramatically changed the region’s land, water and animal populations since then.

Animals

One of the most visible changes is the amount and diversity of animals that live in and around the Bay. In Smith's days, oysters "lay as thick as stones," and the Bay and its rivers contained more sturgeon "than could be devoured by dog or man.”

“Of fish we were best acquainted with sturgeon, grampus, porpoise, seals, stingrays ... brits, mullets, white salmon [rockfish], trouts, soles, perch of three sorts," Smith wrote in his journal. The crew also found a vast variety of shellfish.

Land

During Smith’s time, the land surrounding the Bay was home to a vast array of wildlife: bears, wolves, cougars, falcons, partridges, waterfowl, and a variety of animals named in the old English language that cannot be identified today.

Although native tribes cleared some small plots of land for farming and firewood, much of the Bay watershed remained undisturbed. Smith wrote about bald cypress trees that were 18 feet around the base and up to 80 feet tall without a branch. Some trees were so large that a canoe made from a single tree could hold 40 men.

Water

Unlike the murky summer waters in today's Chesapeake, the water during Smith's time was substantially clearer. Trees formed a thick, continuous canopy around the Bay’s shoreline, holding soil in place and absorbing rainfall from storms. Algae grew but did not overwhelm the Bay’s ecosystem as it does now.

In the 17th century, the Bay constantly shifted with the rhythms of nature—a delicate yet dynamic balance.