Trash Trawl hauls microplastics from Bay waters

A research effort seeks to determine the extent of plastic pollution in the Chesapeake

On a warm day last September, Julie Lawson, Director of Trash Free Maryland, sat on a boat, motoring from a dock in Annapolis. She was surrounded by guests she had invited, and as she spoke to them, a mason jar full of algae-thick water sloshed in her hand with every gesture.

Looking more closely at the jar, several small flecks of white floated at the surface, occasionally sticking to the side of the glass. They were pieces of microplastic—degraded bits of waste less than five millimeters in size. Microplastic is a potential threat to marine life, which can mistake pieces of waste for food. It can also absorb and release harmful chemicals.

“It's funny, I actually started out by caring about trash in the water, and most of the time now all I do is talk about neighborhoods,” Lawson said.

The previous fall, Lawson had collected several similar samples from the Chesapeake Bay with grant support by the Chesapeake Bay Trust and with the help of Stiv Wilson, Campaign Director of The Story of Stuff Project. The result was a visual demonstration of what happens when trash on land gets washed into streams, rivers, and ultimately the Bay and the ocean.

Returning to the water after winning a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Lawson, Wilson and Dr. Chelsea Rochman, an ecotoxicologist and postdoctoral fellow with the University of California, Davis, included more sites from throughout the Bay, in order to obtain 60 samples. Half of the samples would be sent to an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lab for scientific analysis.

The process, in a protocol developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), uses what’s called a manta trawl with a 20x60-centimeter opening and a 333-micron mesh net to skim the water surface for exactly 15 minutes at a time.

"Then I sampled wastewater that drains into the bay from from urban runoff, agricultural runoff and wastewater treatment plants to see if there was microplastic in these sources—and if the type and shape matched with what we saw in the Bay," said Rochman, who also sampled oysters last summer.

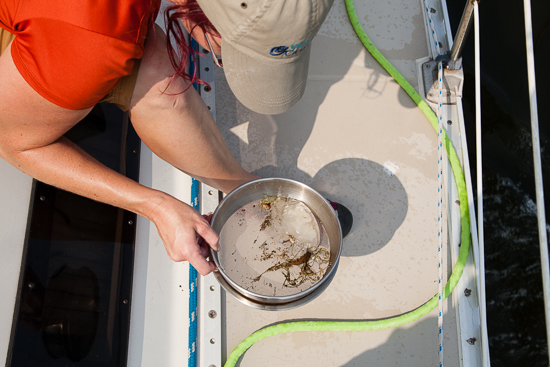

The manta trawl samples include everything from underwater grasses and fish eggs to a pair of sunglasses and a lighter. Pulling on plastic gloves that day in September, Lawson fought her nerves while handling a jellyfish that ended up in one jar. She didn’t get stung.

Lawson said the research will help determine how much plastic is in the Chesapeake Bay, which would set a baseline to help determine if the level of pollution is going up or down. They also want to know the types of plastic, which would provide insight into where that plastic is coming from.

“Is it film? Is it microbeads?” Lawson said. “What kind of chemical is it contaminated with?”

Lawson expects to have lab results from the trawl later this year. The last phase of their study will examine the digestive tracts of fish species frequently caught by fishermen, in order to determine how much plastic the animals are consuming.

To view more photos, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Flickr page

Comments

There are no comments.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories