Photo Essay: Climbing aboard the Learning Barge

Virginia students get hands-on with the Elizabeth River Project’s million-dollar floating classroom

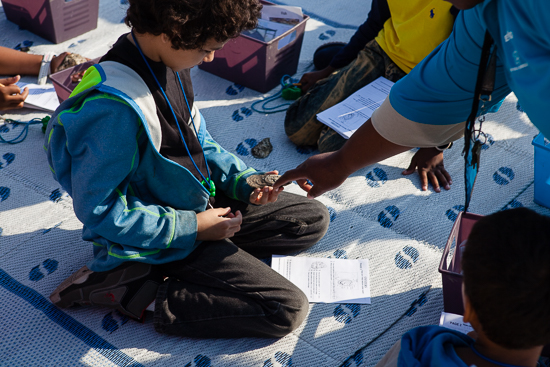

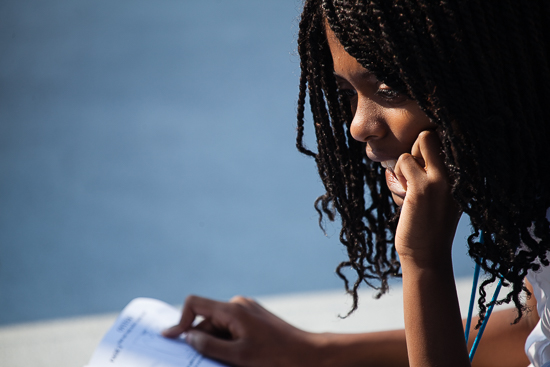

On a fall morning, a lot is happening on the 120-by-32-foot steel deck of the Elizabeth River Project’s Dominion Virginia Power Learning Barge. A stream of fourth grade students from Granby Elementary School follows Robin Dunbar, the Elizabeth River Project’s deputy director of education, onto the vessel via a narrow boardwalk at the Grandy Village Learning Center in Norfolk, Virginia. After splitting into groups, they measure oyster shells, they listen to osprey calls, they find periwinkles in the wetland observation pool and they make traditional mud art in a small classroom onboard. With solar panels above their heads, and captured rainwater below their feet, students on the Learning Barge get excited about their local river—and how they can impact it—in a space that is smaller than a basketball court.

The Learning Barge launched in 2009 and has seen almost 60,000 students—about 10,000 a year—according to Dunbar. She floats from group to group as staff guide lessons on how to build a nest like an osprey or how to use buckets to collect water samples.

“All this was going to be a big wetland,” Dunbar says, standing on the partially-covered deck, which was designed by the University of Virginia School of Architecture and is organized into six indoor and outdoor learning stations for the barge’s 2015-2016 fall and spring programs. “I had a different idea and worked with U.Va. to turn it into a classroom.”

Before there was a barge to build on, the Elizabeth River Project had to grapple with the financial realities of owning and operating such a sizable vessel.

“The [Elizabeth River Project’s] board was very concerned about maintenance in the beginning,” says Marjorie Mayfield Jackson, executive director of ERP. “But the ship repair community, and the tug boats—the maritime community—has adopted the barge.”

It takes about $200,000 a year to operate the Learning Barge, but the cost would be significantly higher without all of the volunteers involved. For example, Jackson says the Elizabeth River Project has never paid for transporting the barge, which is not self-propelled. Last summer, Colonna’s Shipyard donated a paint job for the hull—a value of $40,000. And every winter, BAE Industries takes the barge into their shipyard and asks what projects need to be done.

The sum of the Learning Barge’s parts, which are powered entirely by solar and wind power captured onboard, contribute to a meaningful watershed educational experience for students in the Norfolk area—including several low-income school districts—who may have never really spent time on a river despite living so close to one.

“It’s all science but it touches on different grade levels and they’re able to go back to the schoolhouse and apply some of that to what they’re learning the classroom,” says Marquita Fulford, standing at the Chesapeake Gold station, where students trace and measure oysters. A second-grade teacher at Camp Young in Norfolk, Fulford is in her third year working with students on the Learning Barge.

“Hands on activities, they love those,” Fulford says. “And they remember them—more so than somebody just talking to you.”

To view more photos, visit the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Flickr page

Photos and Text by Will Parson

Comments

i am one of the kids there. im the kid in the white striped collar in a blue jacket no joke

These are beautiful photos of the barge and the children who visited it. Their looks of intense interest and concentration say it all: Hands-on learning is meaningful and effective. Thank you for sharing this story!

WOWWWW WILL - FABULOUS!!! Thank you for such a beautiful essay about our Learning Barge. We want all the pictures please - best ever!!!

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories