Ospreys’ return signals spring on the Bay

Despite long-lasting pollutants, the Chesapeake’s fish hawks are thriving

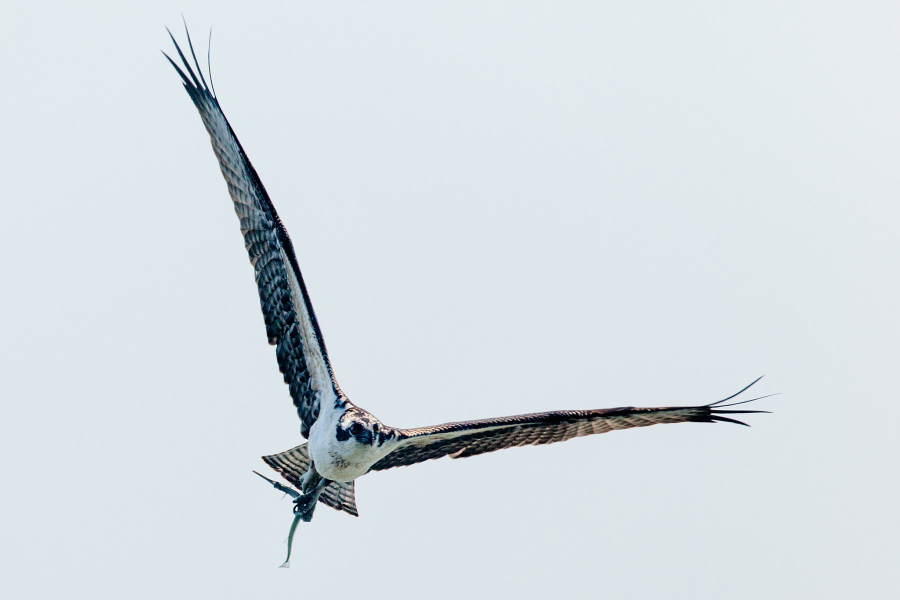

An osprey carries away a pipefish it snatched from Knapps Narrows near Tilghman Island, Maryland, in mid summer. Also known as fish hawks, ospreys are harbingers of spring in the Chesapeake Bay region. The raptors begin arriving in early March and remain along the estuary’s shorelines, rivers and marshes through late summer.

In the mid-twentieth century, the widespread use of pesticides and industrial chemicals led to the near-collapse of the Chesapeake’s osprey populations. The pesticide dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane—known commonly as DDT—was causing female ospreys to lay eggs so fragile that they cracked under the parents’ weight. By 1972, when DDT was banned in the United States, there were fewer than 1,500 pairs of osprey in the Chesapeake Bay region.

High levels of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, have also been found in the eggs and chicks of ospreys that nest along the Bay. These industrial chemicals act as flame retardants and have been used in the production of inks, adhesives, sealants and caulk. While PCBs have not been produced in the United States since their ban in 1977, their ability to persist in the environment means the chemicals continue to be widespread in the region—and can expose ospreys to potentially harmful residue.

Despite the threat of these long-lasting pollutants, recent research has shown that ospreys are thriving in the Chesapeake Bay. As many as 10,000 pairs of the resilient raptors breed in the region—close to one-quarter of the osprey population in the contiguous United States.

As part of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Toxic Contaminants Workgroup is working to reduce the impacts that chemical contaminants have on the Bay and its rivers—and the wildlife and people that depend on them.

Comments

Hi Sarah, thank you for the lovely comment. It is always nice to hear from readers and see the beauty of the Chesapeake remembered (even out in Indiana!).

The phosphorescence you were seeing in the water could have been any of several species depending on time of year, tide and water quality, but you were most likely seeing dinoflagellates. You can read about different types of bioluminescence in this article: https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/parade_of_lights. If the glow you saw appeared in singular locations rather than dispersed through the water, it may have been a moon or comb jellyfish.

Grew up on the western shore right on the Bay. At 64, I'm learning more and more how that isolated tranquility formed who I am and can imagine who I'll be when I pass on. Daddy was a waterman in it's hayday - 40 bushel limit on clams, abundance of oysters, phosphorous in the water at night. (I'd love to know what they really are and their name). Meanwhile on March 17 of EVERY year, Daddy would sit sideways in his kitchen chair and watch for the Osprey to come home. I don't think he was ever disappointed. Our home was right on the marsh of Jack Creek with the Bay beyond. Home for the osprey was a free-standing - if you can call it that - abandoned duck blind. Every winter we though it was it's last for sure, but it held on, to the appreciation of our family and the osprey!

I have so many memories like this one. Nothing prize winning, but life - real life as as waterman's daughter, and no one to pass these treasures on to. When I'm gone, they are gone. If you need a freelance author for a story or a paragraph that I might be able to contribute to, please contact me. I love to write and feel a tremendous responsibility to tell every tid-bit I can think of that I recall, or that Daddy told me.

Thanks for the Osprey. Thanks for the memories.

Sarah (Crandell) Thomas

originally of Shady Side; now NE Indiana.

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories