Planting for change

First-generation Maryland farmer turns 25 acres into certified organic

As I pull into the Moon Valley Farm driveway in Woodsboro, Maryland, the morning sun creeps over the surrounding corn fields. Delivery trucks sit idle, rattling their engines outside the packing house. There's a warm glow of sunlight accompanying the hushed chatter of farm employees as they load boxes of veggies onto the trucks. The stillness is halted when three excited dogs come bounding out of the house closely followed by Emma Jagoz, owner and founder of Moon Valley, a certified organic regenerative farm.

It’s Jagoz’s 12th year of farming and she’s been on her current property, tucked within the upper Monocacy River watershed, for three and a half years. She has grown her business exponentially since her humble beginnings borrowing a half-acre of her parents’ property in the suburbs of Baltimore County. Today, she’s transitioned 25 acres of the Woodsboro property to certified organic, with another 22 acres in the works.

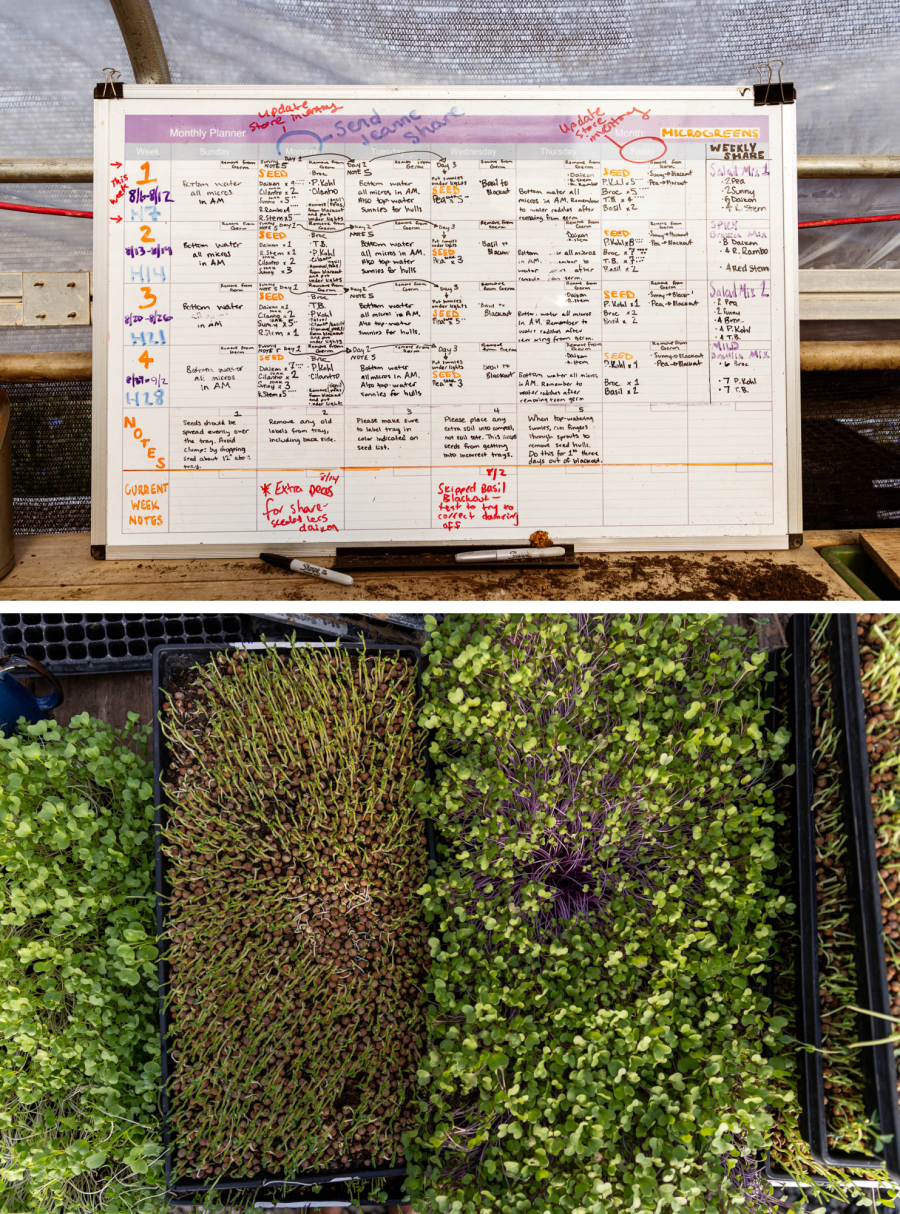

After arriving, Jagoz gives me a tour of the property. The farm consists of isolated sections of sweet potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, herbs, fruit trees, spices, an apiary and much more. Still, Jagoz has plans for expanding her operation.

“Next year, we're taking on additional property across the street. And we will be on 70 acres,” says Jagoz. “We're going to be transitioning those 45 acres to certified organic production.”

With approximately 87,000 farms in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, agriculture is the single largest source of nutrient pollution entering the Chesapeake Bay. However, when farms make use of best management practices, many of which are required by organic farmers, their impact on local waterways can be greatly diminished.

Transitioning a previously conventional dairy farm to organic was a long process that challenged Jagoz and her staff. The certification requires zero prohibited substances such as pesticides and fertilizers, for three years, prior to harvest. This means that Jagoz has to rely on non-chemical means of fertilizing her crops, such as cover crops, compost and succession planting, as well as organic pest repellent methods, such as strategically releasing insects and increasing biodiversity.

Still, for Jagoz, the additional effort is well worth it.

“Primarily, I don't want to put chemicals in my body. And I don't want that for my customers, you know?” says Jagoz. “It's the same with the environment, which is not as separate from our bodies as we think…As anyone who's been a victim of air pollution or water pollution, we are our surroundings."

The rules of organic farming can be strict compared to conventional farming. To ensure that the crops on organic farms aren’t contaminated by non-approved substances used by neighbors, farmers are required to have a 25-foot buffer zone around the perimeter where no crops are planted.

Much of organic farming revolves around protecting and improving the health of the soil. While many farms grow the same crop year after year, Jagoz’s farm produces a variety of crops each season, which adds a beneficial mix of nutrients to the soil. Combined with other organic practices, this supports biodiversity, nutrient density and carbon sequestration, all of which result in healthier waterways.

“In the time of climate change, it is our duty to plant our way out of it,” says Jagoz. “I think agriculture is a big reason why we're here and is the solution to getting out of here.”

After some time walking the property, Jagoz leads me down the hill into a greenhouse with towering rows of sungold cherry tomatoes. The smell hits before we even enter, fresh and sweet. “You know, if you just have a tomato from the field, it tastes amazing,” she says, “and that does translate to nutrients. We evolved to have our tastes correlate with nutrient density, you know, if it tastes better, it actually is better.” She hands me one to try; it was refreshingly sweet and the best cherry tomato I’ve ever had.

“Since the beginning of the farm, I just got so obsessed with the flavor, the taste, and how good it felt and how empowering the whole thing is to be able to grow your own food and really have control over all of that,” Jagoz says, “I wanted to offer that to my community. I know that most people don't have the time to do that, but they still want it. They have other gifts they need to share with the world, but they still deserve to eat that food."

Thankfully, there are numerous people who get to taste Moon Valley’s organic produce. The farm is under a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) system in which members subscribe to receive produce boxes year-round. When Jagoz was farming on three borrowed properties she had 12 members. By 2013 it grew to 25 members along with restaurants. Today she serves over 600 individual CSA members, plus providing produce to restaurants and schools.

“They are the reason that we're in business and the reason that we're able to steward more acres,” says Jagoz. “They are the reason that I, as a single first generation, organic farm mom, was able to buy my own 25 acres.”

Jagoz was not raised on a farm so she learned the skill sets generational farmers are taught at a young age on her own. But being a female, self-taught, first generation farmer comes with its own challenges. Male coworkers are often mistaken for her spouse or the founder of the farm, despite her explaining otherwise. Through social media Jagoz has been able to find support. “There's a lot of women farming, organically, on a small scale, and a lot of them I know in this region,” she says, “so I also feel very confident in the community and the support from other farmers.”

It’s almost noon, the sun is high in the sky, and looking across the fields, the 20 or so employees of Moon Valley are hard at work. Jagoz’s vision of serving and uniting her community through locally-sourced food is clearly in fruition.

“I wanted to do something meaningful,” she says, “It's not a winning game within my lifetime, it's a longer than me game.”

Comments

Lovely to see this story. When I lived in DC, I had the good fortune of subscribing to Moon Valley's CSA for a few seasons. The produce was indeed tasty!

Thank you!

Your comment has been received. Before it can be published, the comment will be reviewed by our team to ensure it adheres with our rules of engagement.

Back to recent stories